Hell Of Troy

Did you ever wonder why the Greeks are called Hellenes? Or where the struggle between collectivism and individualism comes from? There is a deep connection between Easter, Christianity, Marxism, libetarianism, the French revolution, middle class morality, farming, climate change, overpopulation, nationalism and our concept of hell. In short: It all goes back to the Trojan war. And in more than one way, the Trojan war is not over yet. But before we get to the war itself, let’s go back even further, to the dawn of agriculture about 10.000 years ago.

Fertility

Imagine sitting on a hill in the ancient Middle East with your small child. The winter is almost over and the fields are still empty. Soon the sun will be stronger again and the crops will start growing. You tell your child about the cycle of seeding and harvest. “But where are the plants now?” your child asks. What would you reply? If you had the scientific knowledge of today, you might talk about genes and replication, about nutrients in the earth and carbon dioxide in the air. But you don’t have the knowledge of today. You only know that plants go away in autumn and return in spring. “I understand that plants come back through seeds, but where are they before they come back?” Here is what you will not tell your child: You will not try and explain that these plants don’t exist in winter. You won’t, because your child would not understand the concept of non-existence. And chances are, 10.000 years ago you would not understand non-existence either. So where are the plants in winter?

“The plants are still there, but we can’t see them. They are deep in the ground and they will come back through the seeds.” “Why are they going into the ground? What are they doing there?” Would you say that you don’t know? Or that the idea makes no sense whatsoever? Would you tell your child to stop asking stupid questions? Maybe you would. But sooner or later some loving parent will employ a lot of creative imagination and come up with an answer: “In winter, the plants are in another world. They are called to the other side by another sun, which is invisible to us. They grow towards this dark sun and in certain years they stay on the other side. These are the years when our crops don’t want to start growing on our side.” And with this explanation, a happy child finishes a happy day somewhere in the ancient middle east. And it will spread the story of the dark sun to its children and to the children of other parents.

What can you do to call the plants back to our side? It appears that the cycle of harvest is much like the cycle of female fertility. In order to be fertile again, a woman needs to shed some blood. Do the fields need blood to become fertile? Our ancestors thought so. Or rather the subset of our ancestors that had invented agriculture. Fertility can be unpredictable just like a woman. When fertility seemed unwilling, the farmers of the Middle East started bargaining with her. They sent her presents so that she would allow the growth of their crops. They started bargaining. They sent plants into the invisible world of the dead so that other plants would be allowed to return into the world of the living. If that did not work, they sent animals. If that did not work either, they sent humans. Sacrifice was an offer for a deal: We give you something for your invisible world. We hope you are happy now. Please release the crops we need to survive. It was a system that worked very well for a long time. Some years were difficult, but sooner or later fertility appeared to accept the deals offered to her. The crops were growing. Human population exploded. Cities were founded. Civilization was invented. And then it all fell apart.

War

A little over 3200 years ago the first globalized economy of this world collapsed. There were wars before and after this collapse, but the destruction at the end of what we call the Bronze Age was so complete that civilization itself had to be re-invented. Entire nations disappeared. Entire regions of the world lost their memory, their identity, their infrastructure and their role in the world. Almost everything broke down. People were dying everywhere. There was starvation, disease, war. Empires disintegrated from internal conflict. People lost their faith. Some nations simply abandoned their homeland and left into the unknown. What had been built in thousands of years fell apart in less than a generation. Only a few places remained relatively safe. Athens survived somehow. The Phoenicians could defend their strongholds. Egypt was the only empire which retained most of its territory. Everybody else was either dead or thrown back into a primitive existence, without written language and without the goods provided by Bronze Age civilization.

Before this Bronze Age collapse, human civilization was entirely collectivist. What was produced went to the palace. What was needed was distributed by the palace. Life in a Bronze age city was any Marxist’s living dream. There was some degree of private property, but all the main means for production were owned by the collective. This collective was represented by a king, but that’s just what you would expect from a collective: Someone had to define the rules for distributing goods and this one person is king. There was no private farm land. All the land was owned by the city. There were no private farms. There was no concept of a family owned farm. Unless you want to call the entire city one gigantic family. Bronze Age cities had grown out of a collective effort. Everybody in the city was part of this ongoing effort of production and everybody was entitled to goods. There was no sense of individual freedom in a Bronze Age city. If you were not happy, you were allowed to leave and live in the wilderness. Most people decided to stay and play it safe. But then suddenly, within a few years, this was all gone.

Why did it end? In hindsight, the major reason for the Bronze age collapse appears to have been climate change. The conditions for agriculture became worse in the Middle East and there was simply not enough food for all these people in the cities any more. For some years, there appear to have been no proper harvests at all. The palaces had large stockpiles of food reserves, but sooner or later they were used up. Egypt did comparatively better because it was able to hold larger food reserves. But all the other empires collapsed. Some had food for a little longer, but then they got raided by their neighbors. Eventually, people started killing off each other. Which was what they had been doing for centuries, but on a much smaller scale. The invention of agriculture directly leads to the invention of war. If your city is planting crops, you want to make sure that you are also the doing the harvest. You have to defend your land. And if you are running out of food, your only chance of survival might be raiding the stock piles of your neighbor. Every winter, people were using up their reserves. Every spring, they had to make a decision on whether to hope that food will grow soon enough. Or whether they should attack their neighbors while they still had enough power to do so.

And this is how the goddess of fertility also became the goddess of war. Instead of sacrificing their own food or people to the goddess of fertility, people were opting to sacrifice people from other cities. In spring, they would fertilize the fields with the blood of soldiers. What started as an act of desperation, soon became a religious duty: Take the souls of these fallen soldiers, goddess of fertility, and send crops back from your invisible world. The Semites called this goddess Ishtar. The festival of Easter has both its name and its meaning from the sacrifice and prayers for fertility connected with Ishtar. Yet we now ignore the connection between Ishtar (Easter) and war. And this is not simply due to the invention of monotheism. Something else happened to Ishtar which made her lose part of her status.

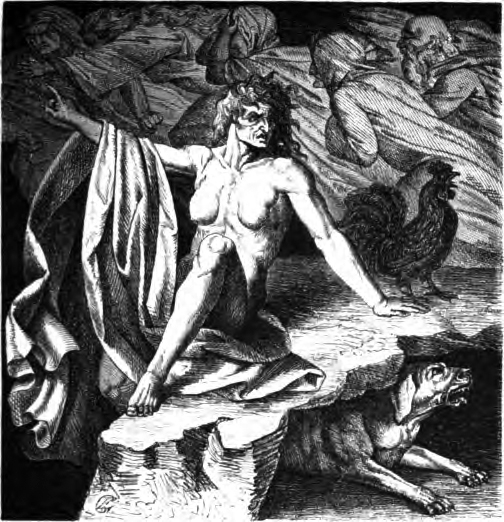

Shame

Before their Bronze Age civilization collapsed, people went through the motions. They tried everything in their book for surviving. And everything they could think of for making Ishtar happy and cooperative again. At first they just did their usual prayers and small scale sacrifices. When this did not work, they resorted to more drastic measures. Their started breaking some taboos. After having eaten everything else, they killed sacred animals. They ate the last grains until they had nothing left for seeding. Eventually, they started eating their own children. But before simply starving to death, the survivors started the biggest war the world had ever seen. A large coalition of nations went to raid the last cities which still had food reserves. Over several years, epic battles were fought. All the nations in the ancient world were involved in this war. It was the first real world war. We know it by the name of one of the cities that were conquered: Troy was able to defend itself for nine years, but eventually was overrun just like most of the other cities. Even the invaders openly admit that they were only able to penetrate Troy’s city walls by engaging in a fraud. The surviving version of this story speaks of soldiers hidden in a religious offer to the Trojans. The Iliad claims these soldiers were able to sneak out of a wooden horse at night and then open the city gates. But Homer’s version might not be the whole story.

The Iliad was written down about 400 years after the war it describes. In the aftermath of the war, people lost most of their culture. They forgot how to read and write. Only two nations retained their written language: Egypt and the Phoenicians. The Phoenicians started colonizing the Mediterranean and we (the West) all learned how to write from them again. But this process took several centuries. People had to bridge the gap with oral history. Which gave them 400 years for changing the story. They had every reason to change it. They had done horrible things. The survivors were the ones who had broken all the sacred laws. They had eaten sacred animals. They had eaten up the seeds for the next harvest. They had eaten their own children. They had killed kings. And they had raided their neighbors using fraud and deception. The soldiers in the Trojan horse were probably not alive when they were offered to the enemy. They had probably died from an infectious disease. The attackers had brought this disease with them and it was killing off their soldiers. But the Trojans were still healthy. So the attackers decided to cram some dead soldiers into a container and send them into the city. Did they really use a horse to do that? Maybe not. Maybe they threw dead bodies over the city walls in some form of wooden container. In any case, the city was probably not opened up by live soldiers but by the disease which had finally started to weaken the Trojans. These kind of tactics were born out of desperation and they were absolutely contrary to the code of honor these warriors were supposed to respect.

When the victorious armies returned home, they were able to save their families. But they were full of shame for what they had done. As the story was transmitted from generation to generation, everybody was feeling ashamed of what their ancestors had done. So they started to change the story. Which left some strange inconsistencies. Why do Ulysses and his comrades cry when they talk about the soldiers in the horse? Wasn’t it supposed to have been an ingenious trick? And why did they start the war in the first place? Because of one woman who followed her lover to another country? Helena is both the official reason for the Trojan war in the official story and the umbrella name of the attacking coalition forces after the war. We call them Greeks today, but that is just the name the Romans gave them much later. In the Iliad, they are called Achaeans, which means water people. They came by sea and their home territory was at the sea, so it’s a fitting name. But after the war, they are called by the name of their war alliance: Hellenes. Helena was supposedly the wife of a king and a daughter of Zeus, but that is still a little too much honor for a lesser goddess. Everything she does in the Iliad would be more fitting for an important goddess. Helena negotiates with gods. The war is fought in her name. In the original story, Helena must have been the main goddess of fertility and war. But later, people were ashamed of what they had done in her name. They did not want to be associated with her any more. Since Helena was the center piece of Greek identity and Greek history, they could not simply delete her from the record. So they demoted her instead. The powers of former goddess Helena were distributed to other gods. Her beauty mostly went to Aphrodite. Her fertility mostly went to Demeter. Her war prowess mostly went to Athene. And so on. The Hellenes of classical Iron Age Greece did not have a proper Ishtar goddess any more. They had hidden her in plain sight.

Heritage

Other nations chose a different strategy. Most of the Hittites simply left. We only know they existed because we have found their archives. The Hittites were collecting gods. With every conquered territory, they added gods to their religion. They also used a mixed writing system. Part of it was based on the Akkadian alphabet. But most of their references to gods are in the form of hieroglyphs or logograms, so we know what they mean but not how they pronounced these names. They have multiple references to the goddess of fertility and warfare. Sometimes hieroglyphs or logograms for her are used. Sometimes her name is spelled out in Akkadian in one of the languages used in the Hittite empire. The Hittites themselves were speaking an Indo-European language, which despite of its age is remarkably close to the Germanic languages. Some of Hittite words are still identical in English or German today. This close resemblance with modern Germanic languages was the reason why Hittite could be deciphered at all. The chief Hittite weather god was for instance typically referred to by his hieroglyph for Teshub, but was also spelled Tarhun, Taru or even Toru. This is our Thor. And Ishtar was sometimes spelled Hal. Which could as well have sounded like Hel, who is the goddess of the underworld in the Nordic pantheon. The word hell is directly derived from goddess Hel. In German, hell means bright, so the German word for hell was transformed to Hölle. We can still see the properties of Helena in our own languages, both the bright and the dark.

The human race has survived the Bronze Age collapse. But people were shocked. They were living with fond memories of a golden age were people were happily living together in harmony. People tried to reconstruct their lost paradise, but on a much smaller scale. They had seen how fragile these over-sized collectivist economies of the Bronze age were. They created miniature versions of a palace economy, hoping that the smaller size would protect them against systemic collapse. This is how the family farm was invented. In a much reduced format, the family farm is the mirror image of a Bronze Age city state. There are fields, there is storage for food and there are animals and metal tools. But the farmer attempts to manage all of that autonomously. All the iron age concepts of democracy, individuality and autonomy are based on the model of the family farm and the miniaturization of Bronze age economy. Small is beautiful because small is crisis resistant. But of course we could not resist the temptation to rebuild our lost paradise. The desire to create collectivist societies keeps coming back. The drive for building a global interconnected economy keeps coming back as well. Ever since the Bronze age collapse, we have seen a constant battle between those who want to return to collectivist societies and those who are weary of their probable failure. Ironically, the collectivists are calling themselves progressives now. Let’s hope our next systems collapse will be less traumatic than the one associated with Hell of Troy. And let’s hope we will learn how to maintain a fertile earth without resorting to human sacrifice again. We have seen it before. We might have to demote our gods again some day.

I wish you and your family a very happy and fertile Ishtar (Easter).